Well, as promised, I’ve got a MicroStrategy 10.7 environment, some shapefiles and some data from the Electoral Commission’s website. So because it’s a cold rainy bank holiday weekend in the UK (surprise, surprise), I’ve been putting all of this together to try and understand what this election is all about.

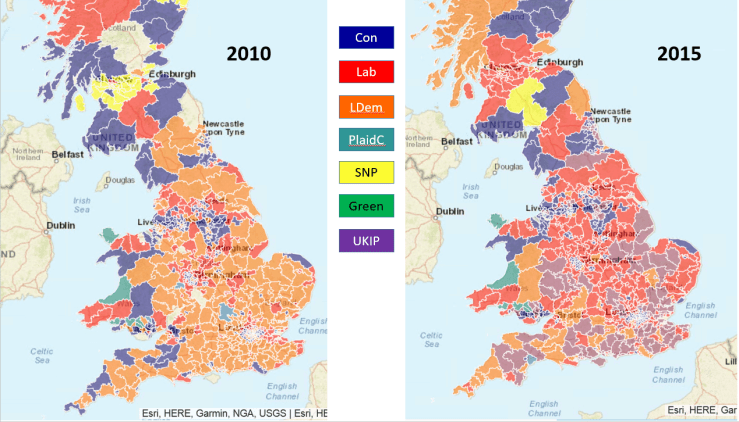

Let’s make a start and compare the 2010 and 2015 general elections. For my dear readers who are not from the UK, the general election is the one that elects our members of parliament. The party that returns the highest number of MPs tends to form the government, with the leader of that party becoming prime minister. It’s quite an important election.

Here we go:

In general, the countryside traditionally votes Conservative whilst the cities trend towards Labour. The Liberal Democrats have a spattering of seats in all areas. At least that was the case until 2015. The election in that year was nothing short of dramatic:

- Labour lost almost all its seats in Scotland.

- The Lib Dems were wiped out, losing a colossal share of their vote.

- The Scottish National Party took control of Scotland.

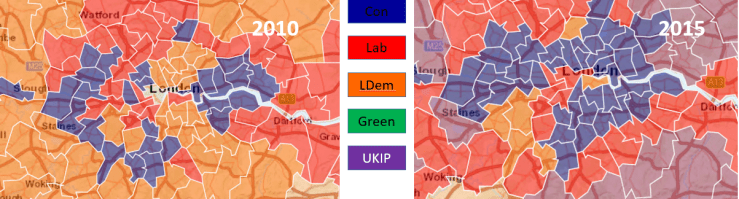

Looking at London:

Again, grim news for the LibDems, losing all seats bar one in London.

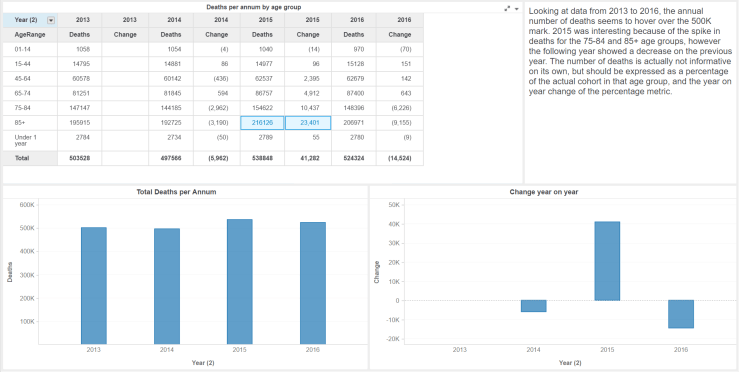

Finishing second is not interesting if you’re an MP (Member of Parliament). But I think it reveals, for 2015, the big change in people’s priorities, and in particular the rise of UKIP. The 2015 election took place before the EU independence referendum, It’s interesting that the data I am about to show you was available then – clearly the Remain camp was not paying attention.

Here’s the parties that were in second place in 2010 and 2015:

Note the very large number of constituencies where UKIP finished second, and the very small number of constituencies where the LibDems reached the same place.

What’s the picture like for London ?

Pretty much the same for the poor LibDems – look at the peripheral areas of London where UKIP is moving up the ranks…

The 2017 election should be interesting because UKIP’s purpose has been fulfilled, and beyond policies trending towards the far reaches of the right it’s possible that the votes that went to UKIP in 2015 may be redistributed. We’ll see…

Commercial Announcement 🙂 ;

I have prepared these maps, and wrangled the data, using MicroStrategy 10.7. I have used custom shapefiles and joined datasets, with derived metrics to work out the share of the votes and the rankings. I will continue exploring electoral data, in particular looking at key battleground seats to assess the social priorities, referendum result and other interesting dimensions. Here, the layers feature of MicroStrategy 10.7 will prove invaluable.

Find out more about MicroStrategy at:

You must be logged in to post a comment.