The Question

Or rather, questions:

Is there a relationship between a propensity to be a victim of crime ( a key domain in the Index of Multiple Deprivation data) and a combination of other, non-crime IMD domains, such as employment, income, education, skills, environment ?

and

Can a machine learning system be implemented to demonstrate and explore such a relationship ?

Commercial Interlude : As I am a consultant working for MicroStrategy, it is natural that I use this excellent software for my exploration. I assume that all the examples here might be repeatable with other tools, but I prefer to spend time on data wrangling and exploration with a system that I know and trust.

What is known

This article is inspired by a delve into predictive metrics conducted a few days prior to the writing of this article. The question posed was initially formulated to provide an exploration framework into the various predictive functions available at the time.

This early exploration provided some useful learning regarding the type of predictive metric, the methodology and the interpretation of the results. It partially answered the question, better success being achieved with clustering than classification.

In particular, the key learnings were:

- In future, cluster all LSOAs (lowest level geographical units) by population density. One of the key findings was that densely populated areas were more successful at being accurately classified as having, or not having, a crime deprivation propensity.

- The Random Forests algorithm appeared to perform best at classification.

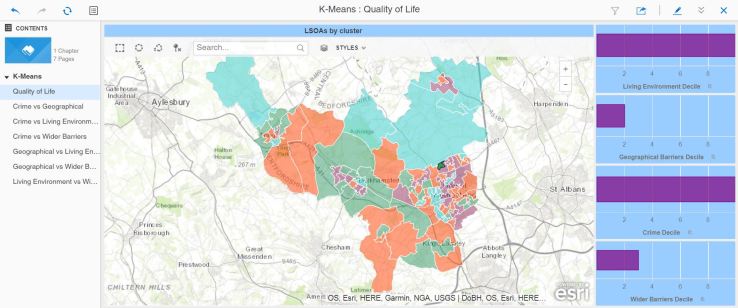

- The k-means algorithm did a good (understandable) job at clustering.

- In future, train and score each LSOA population density cluster separately. A better classification performance is expected – will this be the case ?

What’s Next ?

Population Density

Population density must be a factor in determining a crime deprivation propensity. The classification performance of the initial exploration hinted at a strong relationship between high prediction success rates and high population densities. The density data exists but must be added to the current Index of Deprivation Dataset.

Careful Clustering

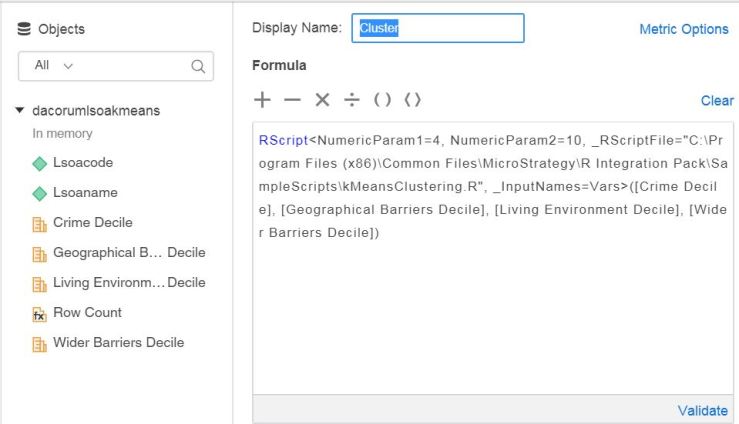

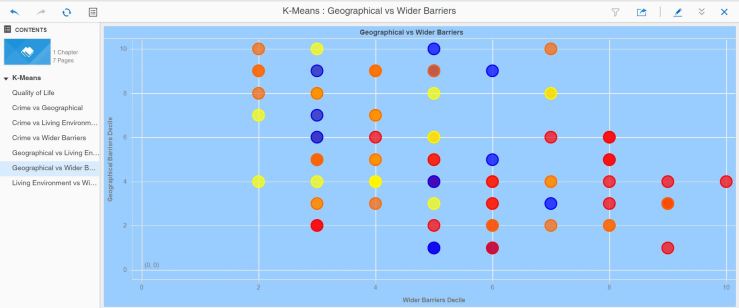

Using population density and other non-crime indices, a number (4 to 8) of LSOA clusters should be identified. The outcome of the clustering needs to be verified for appropriate groupings and the exercise must be repeated with different measures if necessary until the clustering is optimal. Understanding and measuring this optimal clustering in a recursive/iterative manner is possibly key to an AI implementation, but this may be beyond the scope of this new phase. I will continue to use k-Means for now as a clustering method.

Classification Choice

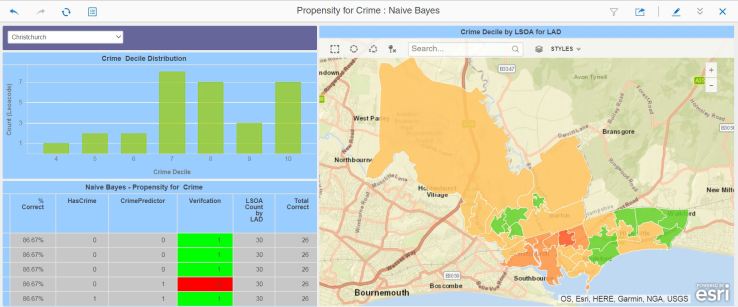

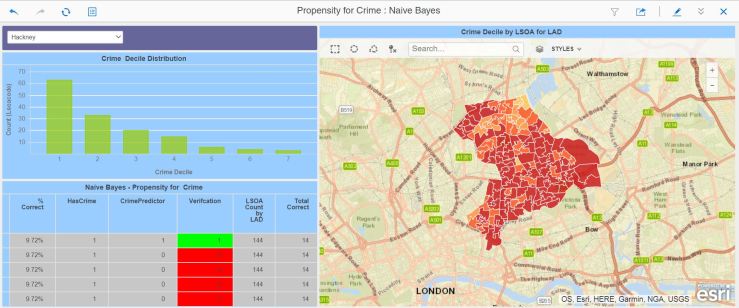

Having had a go at classification using Naive Bayes and Random Forests, I have emerged from this phase with more questions than answers. The difficulty is that the error rate fluctuates wildly, with both methods showing good score accuracy for some LSOAs and terrible for others. The decision lies between improving the existing methods, or trying out a new one. As the name of this blog indicates, this is all about discovery, so I will use the Neural Network R function to score my LSOA cohorts, clustered by the previous exercise.

Progress so far

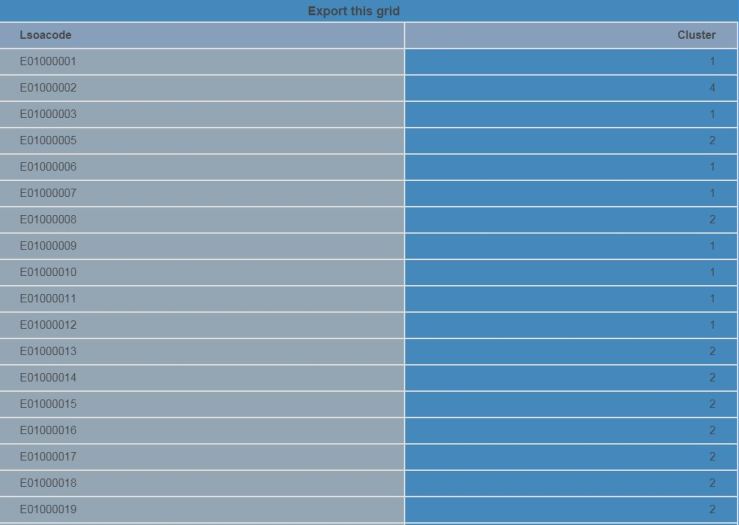

Kmeans based on population density was run and persisted, then added to the main IMD dataset as a permanent segmentation. The clustering was checked out and appeared to make sense based on the metrics used (education, income, employment and population density):

Next, pairs of datasets (training and scoring) need to be prepared for each of the four clusters, and their accompanying dossiers:

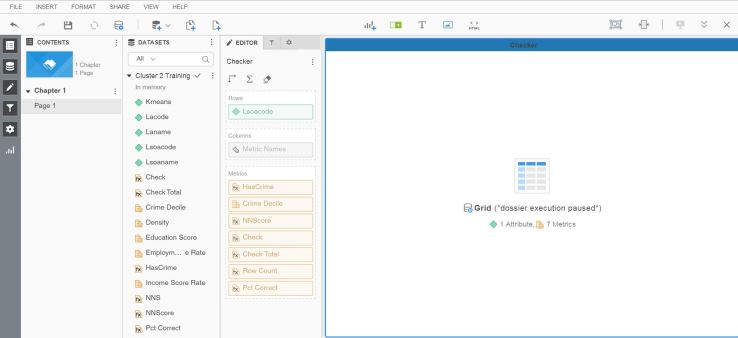

Here is the Neural Network metric:

I am currently working on cluster 1 to verify the mechanics of training and scoring. The areas I am looking at are:

- Number of neural network layers

- Selection of training dataset ( ideal percentage of the total dataset, selection of random LSOAs).

- Understanding why, once I had taken population density out of the set of metric variables, the scoring success rate went from 60% to 91-94%.

- Presentation, formatting and visualisation improvements

When this is done, the cubes and dossiers will be replicated for all remaining 3 clusters.

At this precise moment, however, the findings are interesting enough. A scoring success rate of 91-92%, depending on the number of network layers, is a very big improvement on the initial investigation I carried out with kMeans (no population density) and Naive Bayes.

It’s worth rewording the above paragraph to understand what the neural network approach tells us:

Using clusters based on population density, income, crime, employment and education deprivation scores, for the first cluster tested, it was possible in 91-92% of cases to predict a propensity to be a victim of crime based on income, employment and education indices.

I find this pretty encouraging for a first pass at this particular R function. However, this means an error rate of 8-9% which, if used in real-world impacting applications, could prove to be unacceptable.

Understanding why the scoring errors are happening is, in itself, an interesting discovery process. Discovery means Dossier, of course;

This cluster was the smallest. What will the success rate be on a larger cluster ?

A quick attempt produces the results below, after duplicating the cubes and dossiers, editing the cube queries, repointing the dossiers to the new cubes and saving the neural network parameters to a separate file.

94% in training looks promising. A slightly worrying result is the scoring on the full dataset, which drops to 90% (still good but not optimal).

A point to note here – it’s taking me far longer to write this article than it took to create the datasets and dossiers. All the tech is working just fine, and I suppose my knowledge of MicroStrategy and generally throwing data about mean that I can get from idea to result in a very short time.

Conclusion (For now)

Do you remember the questions posed at the beginning of this article ?

Is there a relationship between a propensity to be a victim of crime ( a key domain in the Index of Multiple Deprivation data) and a combination of other, non-crime IMD domains, such as employment, income, education, skills, environment ?

and

Can a machine learning system be implemented to demonstrate and explore such a relationship ?

In my humble opinion, the answer is yes to both questions:

- Using neural networks, it’s been possible to predict a crime propensity for, so far, about 90-91% of LSOAs. Such an outcome would be of value for a general classification, but for larger clusters an error rate of 10% is a large number of cases which would prove problematic in fields such as medicine or other sensitive domains.

- A series of datasets (in-memory cubes) and dossiers provide the building blocks for an automated scoring application. Quite a bit more work to be done, including writing back to the IMD database and designing workflows in System Manager.

It should be possible to improve this success rate. This relies on the study of the scoring errors, in particular looking at any edge cases and tuning the training data selection and the sensitivity of the boolean crime indicator used as the network target.

Looking ahead

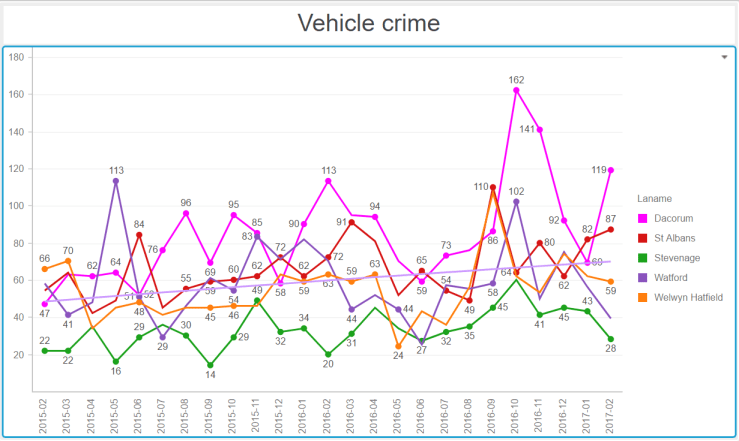

Assuming I manage to complete the work on this, I will use actual crime data at my disposal for each LSOA to verify whether:

- The IMD crime deprivation measure reflects the crime reality,

- The scoring is closer or further to reality than the IMD measure.

In addition, and to keep up with the trend for AI and automation, I can see the value in pointing an intelligent construct at a bunch of tables and letting it do the parsing, clustering and classification on all possible combinations of data items and all results, highlighting the most promising ones, for human discovery and analysis. There seems to be a lot of donkey work in machine learning – automating the data preparation and scrutiny should shorten the time to insight considerably.

Hopefully more news about this soon. Or I may be diverted on another path, you can never tell…

You must be logged in to post a comment.