This article discusses the Prussian, or Clausewitz, Quadrant which was meant to be an army personnel classification method, putting people into four categories based on their levels of intelligence and industriousness.

The two fearsome-looking gentlemen (hover over the pictures to see their names) above are also credited with the invention of the quadrant. See the end of this article for links to Wikipedia articles. I do prefer the picture of Clausewitz, he looks very flamboyant.

I have read about this quadrant in many books and articles, but I have not been bothered to verify its provenance. I still can’t be bothered, by the way, but feel free to confirm or deny its provenance if you must.

Over my career, I’ve had the chance to test the effectiveness of this classification method and have sometimes evaluated my own performance and decision-making based on those criteria.

The thing about quadrants is that they are easy to understand. Being easy, they tend to be a blunt instrument and lacking in depth. Making important decisions on what you see in a quadrant comes with a healthy dose of risk.

Please note that in this article, I am putting my own spin on the quadrant, based on my experience of people encountered throughout my working life.

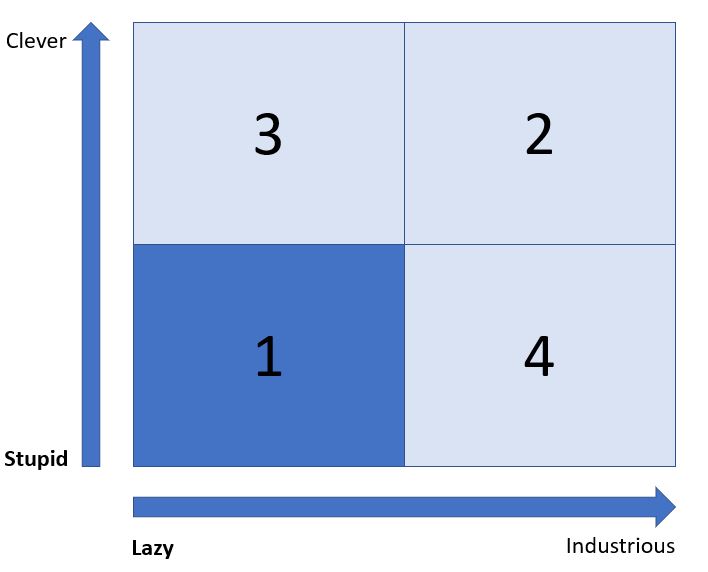

I’ll explain the categories over the next few paragraphs, but let’s start by looking at the Quadrant:

You can see that there are two axes – the horizontal one evaluates industriousness going from lazy to industrious, whilst the vertical one illustrates intelligence ranging from stupid to clever. Because we like simple models, we only plot four areas in the quadrant (hence the name), and we evaluate people based on the quadrant to which they belong.

I’ll mention a key weakness of the quadrant approach in the conclusion to this article.

Now, let’s examine the first category:

The Stupid and Lazy category can be used for people who are not necessarily stupid per se, but are absolutely not engaged and will not invest any of their resources in the organisation in which they participate.

The Prussians found a use for these persons where they would be given repetitive, simple tasks that needed to be done but would frustrate a more capable or invested individual.

Modern organisations may still need such people but automation and AI are definitely in the frame to replace them.

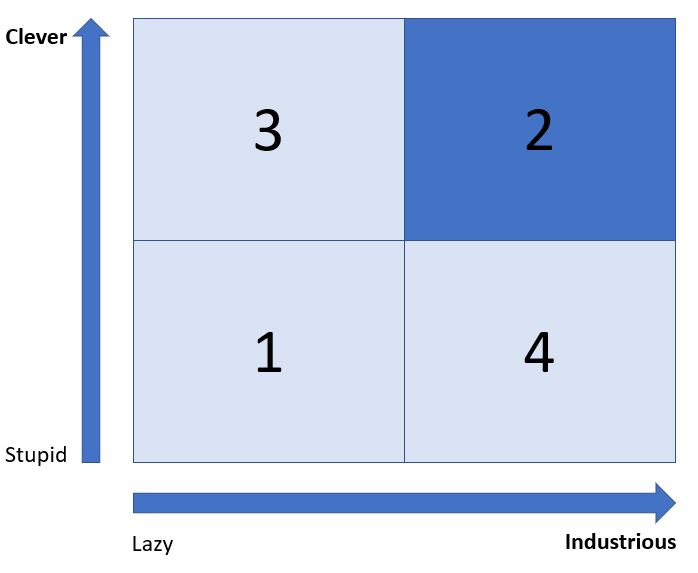

Next, we have:

Being Clever and Industrious is an absolute gift to an organisation. Complex tasks can be given to these people, and they will thrive on the challenge.

Furthermore, they are keen to take on more work but run the risk of burning out.

The astute leader will know how hard to drive and challenge these valuable resources to obtain the best sustainable yield.

Clever and Industrious people can often over-complicate things and will design processes and systems that may challenge those who do not have their capacity for thought and work. They may demand of others a yield that, to them, seems achievable, but would have less endowed individuals working at full throttle permanently. That doesn’t usually end well.

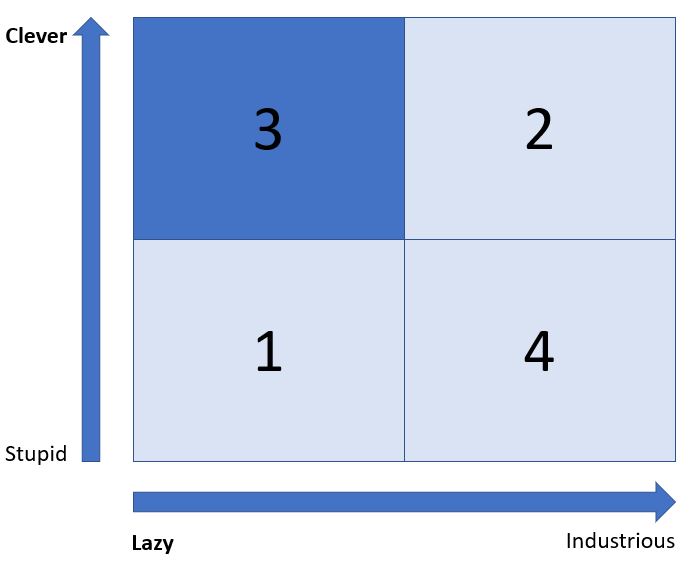

My favourite category is next:

Belonging to the Clever and Lazy category is an attribute that should be valued providing an organisation is not entirely composed of such persons.

People who seek to get the best yield out of the lowest amount of work possible will look for efficiency and simplicity in order to get the tasks done. They are often good delegators.

Clever and Lazy people think laterally and can reach innovative solutions which would elude their more industrious, focused peers.

They need to be led and motivated to keep the lazy side of their nature under control. Promotion is often a method used to get the best out of this category. Being lazy does not imply a lack of ambition and a desire to succeed.

I have left the most dangerous category for last:

One suggestion I have read (not mine, although…) for such people is that they should be shot on sight.

This may be a bit harsh, but there’s no understating the damage that can be caused by someone who is capable of stupidity at scale.

On a less dramatic level, such people could be the ones who follow dogma to the letter and are unable to adapt to unusual or changing situations. They are often a cause of friction and stress when the need arises to be agile or decisive. Another instance of this behaviour can be shown at the higher echelons of leadership where lack of experience or foresight when making decisions can have unforeseen and disastrous consequences.

Such attributes can be self-correcting, in that organisations should eventually divest themselves of such people as the impact of their actions rarely go unnoticed. And sometimes, lack of experience can be mistaken for stupidity. Providing the incidents are survivable and the individual teachable, it should be possible to evolve out of this category. So all is not lost.

To conclude this article:

Classification methods are often unsatisfactory. It seems convenient to put people in neat little boxes, because it allows organisations to devise processes and policies which can be standardised.

I was alluding to a flaw in the quadrant method, in that it permits the presentation of subjective and poorly curated data about a collection of subjects as an absolute and inevitable truth. It is an impressive consulting tool, but the decision maker must drill into the collection and classification methods to assess their validity.

Nevertheless, I like the Prussian Quadrant because, empirically, I have found this classification to be accurate, even if it is incomplete. It is also not a predictor of success, but describes a simple set of behaviours and attributes which can be the starting point to evaluate desirable personnel profiles.

When it comes to success in an organisation, some of the factors I have observed, beyond capability, have been:

-An ability to be relevant to the leaders

-A way of being credible and trusted by leaders and followers

-Skilled in managing upwards while keeping a professional distance

-Delivering results reliably and repeatedly

Plus, really, an ineffable capacity to be heard, to influence thinking and to make sound judgement calls in uncertain circumstances.

You could argue that these capabilities can exist independently from intelligence and industriousness, and may even be present when one or both are lacking. It all depends on the organisation – like people, they tend to be quite individual, despite our efforts to classify them.

I hope you enjoyed this article. I list below a couple of links to find out more (all hail Wikipedia !).

Wikipedia page about Carl von Clausewitz

Wikipedia page about Helmuth von Moltke

Wikipedia page about Kurt_von_Hammerstein-Equord

And a link to one of many articles discussing the origin of the quadrant:

Quote Investigator: Clever-Lazy

You must be logged in to post a comment.