All too often BI developers are so wrapped up in the tech and the process of building their clever, pretty solutions that they fail to see the significance of the data they are handling.

I have been guilty of this on many occasions – a clever chart about type 2 diabetes that shows a pretty grim reality, or a heat map that highlights a probably underpaid or desperate person with their fingers in the till… In all cases, there are people behind the grids and graphs that we handle on a daily basis.

The difficulty with data is that it can either be spun to tell a story, or conversely reveal a truth too awful to bear. A case in point is when data is used to work on areas of discrimination such as race, gender or class. How do you interpret your findings, and how do you handle difference ?

To illustrate this, I am going to pick a contentious area – Gender – and focus on a sub-area of it, education. I do this because in this case the data seems to reveal something pretty wonderful.

The data documents the findings of the Pisa survey, a programme undertaken by the OECD to measure the achievement of 15 year-old children in participating countries.

It’s interesting to note that the survey itself splits the data by achievement for boys and girls. Thus, in the very design of the survey, a difference is acknowledged between the genders and is used for comparison. I am not keen to get sucked into gender politics, as I really do not have any in-depth knowledge of the issue. But as a data explorer, I am quite interested by a few facts revealed by the survey:

- Finland does a pretty good job.

- Girls tend to be more or less achieving as well as boys in Science, but boys appear to pull ahead a bit in Maths.

The most astonishing finding, however, is the vast gulf in reading achievement between boys and girls, with girls way ahead in all countries – and thus all cultures. The survey does state that the gap is closing, with an improvement for boys and a degradation for girls (that last point is concerning).

How do you explain that ? Why is it that girls are so much better at reading than boys ? More importantly, when comparing both, how do you present your findings to avoid falling into a gender bias trap, especially when it comes to difference ?

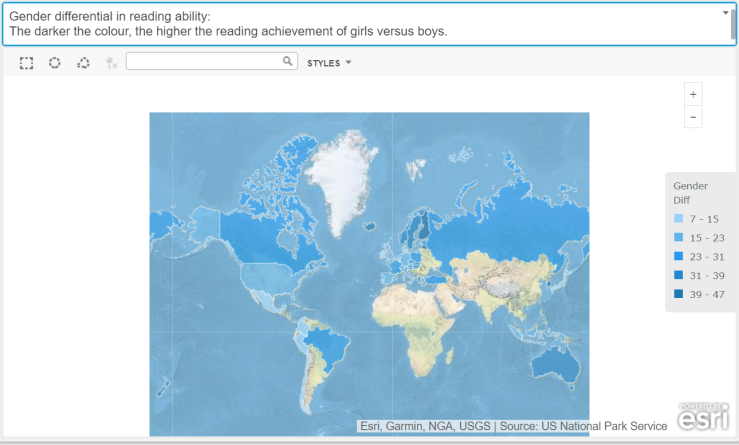

An attempt to explain this is made below with a world map showing the reading differential between girls and boys, with the measure shown as a positive figure (Girl ability – boy ability):

So there we have it. All over the world, girls are reading better than boys. In some places like Finland or Korea, already very high in achievement in all matters, the gap is even more pronounced. Can you deduce that increased education capability results in an even higher reading ability differential ? The data seems to support that.

That’s a good story. But, with the same data, we can tell a different story. Assume that we live in unenlightened times, where we decide that the lagging of reading ability in boys is to be spun as a crisis:

All we’ve done here is that we have flipped the formula (Boy ability – girl ability) and applied a more alarming threshold. Thus, a tabloid journalist can alarm us all by stating that Scandinavian countries are in the grip of a reading crisis of untold proportions.

What was, in the previous illustration, a positive story has now become an alarming picture of male underachievement – whereas the real story, in my opinion, is that girls genuinely do seem to be better at reading than boys.

Why not try this yourself ? The OECD kindly shares its data, so you can download it and play with it in your tool of choice. I use MicroStrategy (I work for them) for all my data discoveries – you can download the Desktop version for free here:

You must be logged in to post a comment.