Information wants to be free – but an enterprise needs it to be like a life-giving stream of sustaining insight, rather than a thin trickle of stale data or worse, a tsunami of garbage. Maintaining a robust, innovative and flexible ecosystem in an ever-increasing whirlpool of data represents a daunting challenge. Just as software development practices have moved away from waterfall methodologies to agile practices, an enterprise business intelligence system has to introduce velocity whilst preserving veracity. It’s clear to see that the traditional DEV/TEST/PROD lifecycle is no longer the whole solution, but what does the alternative look like? This article describes the evolution of business intelligence lifecycles and prepares the ground for a further study of implemented practices.

Having your cake and eating it

System of record outputs must be truthful and resilient if they are used for regulatory purposes, or if they are part of mission-critical business processes. Yet, timely and volatile insights are also key to fine-tune the steering of a business process – think about a mobile phone company needing to know the take up of a new tariff or device, or modelling the impact of new financial regulations about risk on a banking portfolio. This information is needed now, not three to six month down the line after a laborious waterfall process involving many separate, thus siloed, teams.

That problem is solved with modern tools allowing governed data discovery and process differentiation between system-of-record outputs and ad-hoc or exploratory products. If your current system is not capable of doing this, you need to ask yourself why…

Yet, as always, the world does not stand still. You congratulate yourself with the achievement of a governed data discovery solution, and here comes the data lake!

This throws up a completely new challenge because you want to avoid a proliferation of exploration and exploitation tools, and you also want to keep a grip on the potential explosion of new applications. From my perspective, I’ve heard about Data Lakes and Big Data for quite a few years now – but now, we’re encountering these in increasing frequency. So how do we handle these?

What’s the data lake for?

I’m hoping that the data lake is a familiar concept for all – there’s been enough stuff written about the subject. The best question to ask is: what is it used for? I’ve seen two broad use cases so far: Genuine exploration of colossal amounts of unstructured data, and replacement for Data Warehousing appliances.

The first case is about shoving pretty much any data in the lake, and using tools and processes to make sense of it. The second case proposes that storing colossal data warehouses is more cost effective on Hadoop technologies than more traditional large-scale solutions. You’d be correct in thinking that a data lake can address both use cases, but you’ll need to solve the veracity and velocity gradients inherent in both cases: Exploration is done by few, using unpredictable and intensive processes, yielding insights and results which may be volatile. Exploitation, the second case, is used by many and requires resilience and veracity enforced by governance.

Where is it going?

I don’t have the answer – yet. The installations I have seen are still in their infancy, and exploration is not simply limited to the data, but also to the processes and governance that have to be developed if a smooth and repeatable transition from exploration to exploitation is to be achieved. What I will try to do in this article is to map the evolution from highly governed implementations to those I see emerging today, with governed discovery and data blending between systems of record and exploratory data lakes.

Business Intelligence system evolution

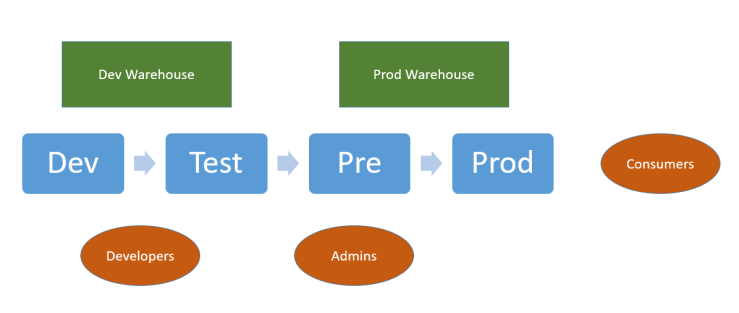

In the beginning: The traditional setup

This environment provides consumers with highly governed outputs. Change control and governance are strongly enforced – new developments go through extensive testing prior to reaching the end users. Thus, robustness and resilience are the strong points of such environments, whilst the weak points are agility and velocity. New data or functionality take so long to evolve that end-users declare independence and branch off on tools outside the corporate-mandated toolset. Not surprisingly, such systems are getting increasingly rare these days.

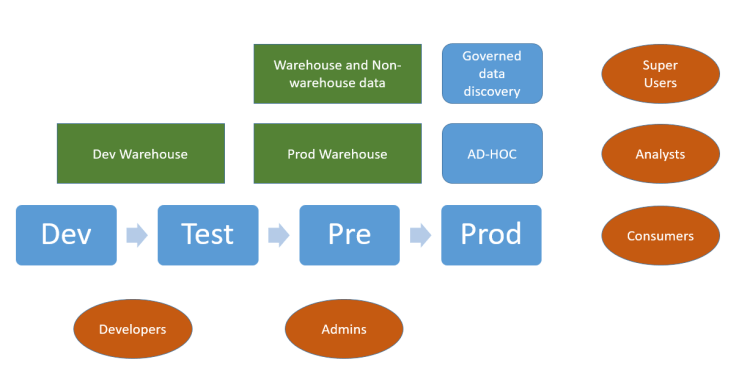

Reluctantly, some freedom for privileged end users

Here analysts are given freedom to develop their own offerings but these are all based on central data. This allows for different versions of reports and dashboards, but does not address the need to rapidly model new data and exploit it. Resilience and robustness are preserved. Agility is introduced, with a small risk of divergence from the single version of the truth. Users will still work outside the system on new, volatile data. Governance becomes more complex as many new reports, and versions of those, proliferate within end-user folders.

Today: Freedom expands at a fast pace with new data and new challenges

Today we can add external data to the mix, and a new type of user (the Super-user) is empowered to import new data and blend this with system of record data. This brings into the enterprise solution the previously delinquent users who employed other tools to get results. This also increases velocity, but introduces a veracity gradient if the offerings from the super-users, based on blended data, start diverging from the governed and curated corporate data. Kite-marking ensures that outputs from the system-of-record process are recognised and differentiated from the ad-hoc, agile offerings.

Your strategic toolset should provide you with the necessary functions to identify ad-hoc, agile offerings that start to scale and become part of key business processes. These offerings are then prime candidates for being fed back into the system-of-record process loop, as they can be industrialised and made resilient for the larger consumer community. This also ensures that a solution does not become dependent on one individual – the creator – but can instead be supported and maintained by the developers and the admin teams that look after the system-of-record process stack.

Another feature of this environment is that the load on the production servers becomes less predictable. As development and application architecture become less centralised, your enterprise tool must have the capability to govern and scale up in a safe manner. Whilst the development bottleneck is reduced, the administrators will have new tasks in identifying and restricting the resources that these new users can employ. This restriction may be an issue, and still cause point solutions to be developed outside of the enterprise solution.

Such systems, rendered possible by advances in the best enterprise business intelligence tools, are becoming increasingly common.

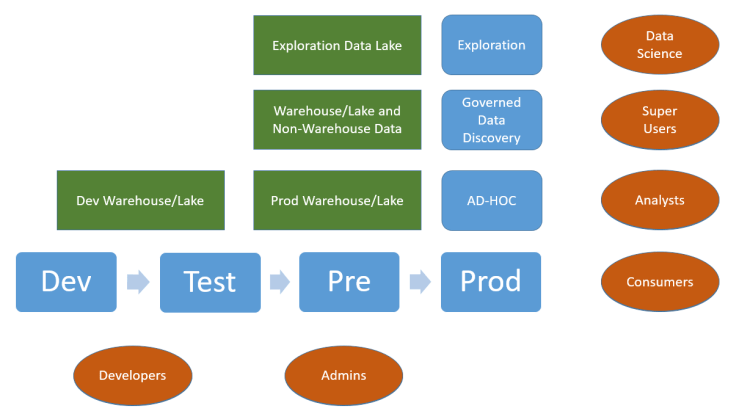

And then: Big data happens

As stated in the introduction to this article, in some cases the data lake is used as a traditional data source and thus becomes tied to the core system-of-record process. It’s when it’s used for exploration that yet another cohort of users, the data scientists, can use the enterprise tool to launch exploratory queries to gather new insights. What’s happening now is that we have, in addition to the traditional dev/test/prod lifecycle axis (the exploitation axis) another axis for exploration, as shown in the diagram below:

Our consumers are now at the confluence of two types of output: System-of-record offerings, strong on veracity and engineered to scale, and exploration offerings, high in velocity but not necessarily scalable or resilient. This poses a challenge: Our consumers range from shop/branch/store users all the way to executives. Our offerings need to come with a quality rating so that the end user understands how the insight was produced, and that there is a difference between high-velocity, high-volatility outputs that will not have gone through the engineering and resilience rigours that the system-of-record items will provide.

Volatility is the key concept here. It relates to the persistence of an offering. If it is transient, needed for a short period of time only, it should be treated as such and not much effort should be put into making it scalable and/or resilient. Conversely, if an exploration-originated offering starts to be used by many people, and becomes an essential part of key business processes, then it must be integrated in the system-of-record domain by shifting it from the exploration axis to the exploitation axis.

Your enterprise solution should provide you with the necessary tools to identify offerings that are used frequently and the relevant consumer cohorts. You should then set thresholds by which a decision is made to take the exploration offering and send it through the exploitation process to make the offering scalable and resilient. These actions are represented in the diagram above as the ‘persistence assessment process’.

What’s next?

Observation and learning

The last diagram shows where some of our customer’s systems are at today. This represents a rapid departure from lifecycle orthodoxy, and requires new processes for governing and administering the system. The administrators will need to monitor the load on the production systems and provide the information necessary to identify offerings to be industrialised. Development will be devolved, in that the data scientists and super users will be creating the first drafts of new applications based on production data. The task for traditional developers should be simplified and these should become more productive as the requirements are better understood.

New system topologies

The sacrosanct production environment will still exist, but it may be cloned to support the exploration process. This mitigates the risk that intensive exploration and implementation poses to the production environment’s stability. This may increase the administrative workload so you will need to make good use of all the helper tools offered by your enterprise solution.

Free flow of ideas

As an interesting historical analogy, it is now certain that the reason that the Industrial Revolution took place in the United Kingdom rather than France, for instance, is due not to the lack of scientific and technical competence – France had, in the 18th century, a huge cohort of world-changing scientists and innovators – but to the free flow of ideas and a loosening of central governance, supported by an enlightened leadership. France centralised everything and took for ever to release new knowledge, whereas British entrepreneurs simply got on with it.

It may be a bit of a stretch to compare an enterprise business intelligence system to a country – but you do notice the harm done by sclerotic processes to innovation and the sharing of information.

Keep the lid on

Conversely, you can also judge the effect of a proliferation of false information, as events in the US election or the EU Referendum in 2016 have shown. This leads to uncertainty and mistrust, which not desirable in an enterprise setting.

This highlights the importance of a good governance framework, and of educating the consumer to rate the veracity of system outputs based on their source.

And finally…

This is very tantalising, but you might well ask how this Business Intelligence utopia can be achieved. Right now, some of our customers are setting off on this journey – so over time I hope to be able to revisit the topics shown in this article, and maybe share some good practices and highlight some bad ones.

Until then, try not to drown in your data lake!

You must be logged in to post a comment.